Things I learned studying the cell cycle in cancer

Samantha G. Zeitlin

I know that from the outside, ‘science’ seems like The Place Where Scientists Live. But ‘science’ is not a monolithic, homogenous thing. Not all scientists are the same.

Today someone called me a Biologist. But I was never really a Biologist. My undergraduate degree was in a chemistry department.

My past life as a researcher was always very interdisciplinary. To better understand cancer cells, I used a lot of sophisticated software, and mathematical intuition, in addition to chemistry and physics.

Do the math

Asking good questions in science often starts with some back-of-the-envelope calculations. For example, in the human body, there are approximately 10,000,000,000,000 cell divisions per day. Some cell types are always dividing.

There are about 3 billion base pairs of DNA in each human cell.

Replication is very messy! There are about 1000 chances for mutations at each nucleotide in your DNA, every day.

So how do we even survive?

It turns out that the relatively high fidelity of DNA replication actually comes from systems that recognize and repair mistakes.

And, we’re constantly being exposed to sunlight, pollution, and other chemicals that damage DNA, like cigarette smoke and alcohol. DNA damage happens constantly. Life is hard.

It turns out that the cell cycle is a really interesting population and time series problem. The average human cell takes about 24 hours to divide. The main goal of cell division is simple: information is propagated from mother to daughter cell by DNA. The DNA is replicated so the daughter cell can have a copy, and that DNA is organized into chromosomes to make it easier to distribute. There are a lot of chromosomes, especially in cancer cells, which tend to have extra chromosomes.

Before cells divide, each pair of replicated chromosomes gets a type of ‘handle’ to help the cell pull the copies apart.

Cells use what we call checkpoints between the stages of the cell cycle, to make sure that the right things get done as all the parts are replicated and ready, before moving forward to the next stage.

The actual division step only takes about 1 hour. The other 23 hours are preparation.

How to study an ongoing cycle

In some ways, the cell cycle is like a live web service. It’s running all the time. You might have many copies, all out of sync. A population of cells is much like that. Or a population of customers.

If you want to study a time-dependent process, you basically have two options:

1. Stop it. Just stop it.

With cells, stopping the cycle is done using drugs that trigger cell cycle checkpoints. This is the basis for some cancer drugs, since stopping cells long enough will cause them to give up and die.

With a web service, you might take it offline, or just use a mock version of the site.

It’s obvious why this is a simple approach, which makes it appealing.

But it’s also artificial, and doesn’t represent what really happens.

There can also be side-effects of the interruption.

2. Watch. Just watch.

With cells, watching usually means using a microscope, and sampling.

With a web service, this would mean using surveys to ask your users what they think, or adding beacons into your embedded videos that send back information when someone clicks on them.

There are two main advantages of observation:

• Get closer to the real thing: the system isn’t artificially disturbed by the process.

• The opportunity to see something you might not have known to look for.

The disadvantage of observation:

It can be a little more complicated to do the analysis. It usually requires a little more math.

What wastes the most time?

As a researcher, I had to be highly organized. The kinds of experiments we did were laborious and expensive, and we never had enough funding. In research, you get used to screwing up a lot, but you’d rather screw up because your hypothesis was wrong - because at least then you learned something - than because you didn’t plan ahead.

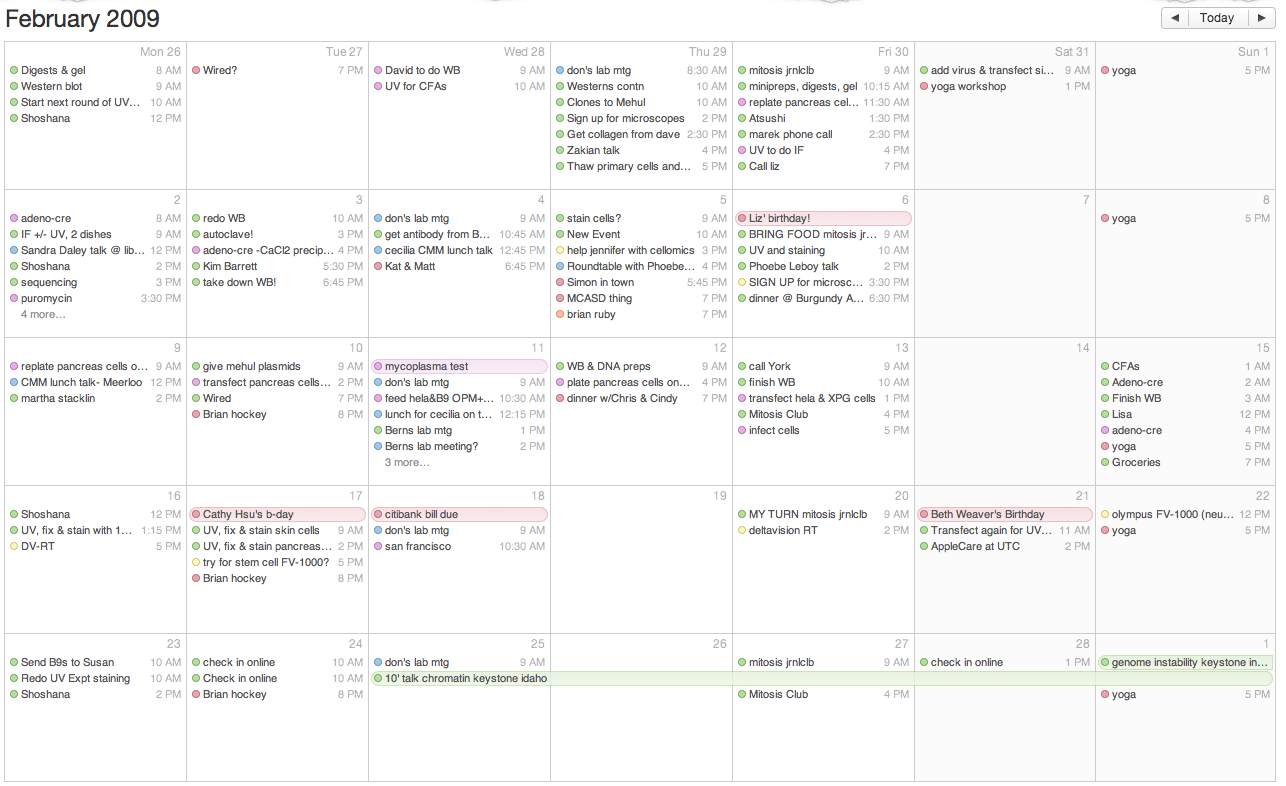

My calendar was always full. Here’s a screenshot of a typical month from when I was a postdoc:

So I put a lot of effort into trying to figure out how to get the most bang for my buck, in terms of how to design my experiments to be informative, making sure I had everything I needed for the more elaborate ones (especially the time-sensitive experiments), and trying to do it all on a shoestring budget.

Here’s what I realized. The one thing that wastes the most time:

False negatives.

Using the wrong approach: the hypothesis seems to be wrong, when actually the experiment failed for technical reasons.

False positives are easy to test: just do the experiment again. If it’s not consistently reproducible, the end. Move on.

False negatives, on the other hand, take longer. Because a different perspective seems to be needed, a false negative often results in a long tangential trip in the wrong direction.